Introduction

In both journals, art plays a prominent role. From poetry and photographs to drawings, these elements add meaningful insight into the thoughts of their creators and provide a practical way to convey visual information. Read on to learn about these different art forms!

Poetry

Nellie Martin Wade included a poem about Denali (referred to by Wade as Mount McKinley) in the tenth chapter of her manuscript, which she penned upon viewing the mountain for the first time.

Having ever been a lover of Nature in all her forms and moods from the tiniest wild flowers and the most delicate ferns to her great forests, her mighty rivers, and her wondrous mountains, no sight ever impressed me more than this noble lofty peak. I could not refrain from writing these lines as a tribute to her serene glory fully, realizing that no pen has power to describe, nor, brush to paint, any thing that can justly describe such magnificent grandeur.

I gaze in awe and silent admiration,

McKinley, Grand old Mount, at you today.

You rear your head, majestic, towering Heavenward

As you’ve done for countless ages passed away.

O mighty monarch, when I first beheld you,

Your wondrous form uplifted to the sky,

Your hoary head aglow with God’s great sunlight,

Reflecting glory on all peaks near by.

Marveling, I wondered at the power, old mountain,

That could create your rocky sides so grand.

Thou art a temple; Yea a shrine eternal;

Mute witness unto God’s omnipotent hand.

O Mount, your snowy crown so far above me,

So noble, grand, inspiring, aye, sublime,

Has tuned these myriad voices all around me,

To sing eternal praise of the Divine.

The gentle breezes sighing through the pine trees,

The brooklet murmuring on its lonely way,

The bees and birds afar off in the woodland,

All join in one sweet harmony of praise.

Yea, all grand things, both great and small about me

Pay homage to you, dear, old mount sublime.

Your glaciers, streams, your trees and e’en the daisy.

Thou silent monarch, prince of power and time.

For man beholding you in reverent wonder,

A few short years has spent his fleeting day.

While thou endurest supreme in kingly glory.

Eternal! Till all time shall pass away.

Religious and royal imagery is consistently present in each stanza of the poem. Wade writes that her words are not sufficient to express the mountain’s impressive nature, and her references to God and a monarch, two figures often viewed as indescribable and above all other humans, emphasise this perspective. Simultaneously, she includes a stanza that reflects a remarkably calm, feminine perspective, referring to “gentle breezes” and “sweet harmony,” revealing a less intimidating, but still spiritual, way of viewing the mountain.

To better understand Wade’s poem, we can turn to the words of another explorer, Frederick Cook, who encountered Nellie on her journey and whose journey is discussed in the journal. (To learn more about Frederick Cook’s connection to Wade’s trip, head to Purpose of the Journals.)

While researching Cook, I found the article “Frederick Cook, Mountaineering in the Alaskan Wilderness, and the Regeneration of Progressive Era Masculinity,” a discussion of Cook’s experience climbing Mt. McKinley, based primarily on Cook’s published work on the expedition. Bayers connects Cook’s journey to American masculinity and reflects on Cook’s spiritual view of summiting Mt. McKinley. Cook shares Wade’s view of the mountain as “sublime,” and refers to his summit of the mountain with many references to heaven. The physically demanding experience brings Cook closer to the divine, and Bayers reflects on how the resulting sense of triumph over the mountain carries over to the goal of settling Alaska and fulfilling Manifest Destiny. Though Cook’s writing may emphasize the climbing of the mountain, it shares the awe present in Wade’s poem.

Reading Cook’s journal, I found his reflection on his own reaction to Mt. McKinley at the start of the eleventh chapter:

There are mountains where the blend of colour, the scale of dripping waters, the waves of balmy breezes run to music and poetry and quiet aesthetic inspirations, but there is no such play on the senses here. Mt. McKinley is one of the severest battle-grounds of nature, and warfare is impressed with every look at its thundering immensity. The avalanches fire a thousand cannons every minute and the perpetual roar echoes and re-echoes from a hundred cliffs.

The imagery of violent war contrasts with Wade’s delicate stanza on the calm forest, and Cook claims that Mt. McKinley is not suited to the artistic representation that Wade provides. It is possible that this difference in perspective results from the physical differences in their journeys, and that Wade might not view the mountain as favorably if she too climbed it. However, it is also possible that Wade’s feminine perspective inspires her to create more palatable ways of conveying her experiences.

The poetry also mirrors the style of Fireside Poetry, a mid 19th century genre carried by five poets that was the first type of American poetry to gain mass popularity. Their poems followed strict but simple rhyme structures, and were often read together by families or used to teach young children to read. “Paul Revere’s Ride” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow is one of the most famous examples of Fireside Poetry. Wade’s focus on nature and rhyme scheme seen in each stanza reflect the style of Fireside Poetry. It’s interesting to see how Wade was influenced by American culture that preceded her, and the ways in which this style of poetry is associated with American ideals similar to those Wade addresses in the journal.

Photography

Alongside her poem, which provides textual imagery for her journey, Wade includes numerous references to photographs in the margins of the manuscript. While these photographs are no longer found alongside the journal in its current location in Special Collections, the detailed list located at the beginning of the journal titled “Illustrations” describes 46 images that are cited throughout the journal. Since Wade credits two men for photographs at the start of the journal, it is likely that these “illustrations” refer to photographs, rather than drawings or other artwork.

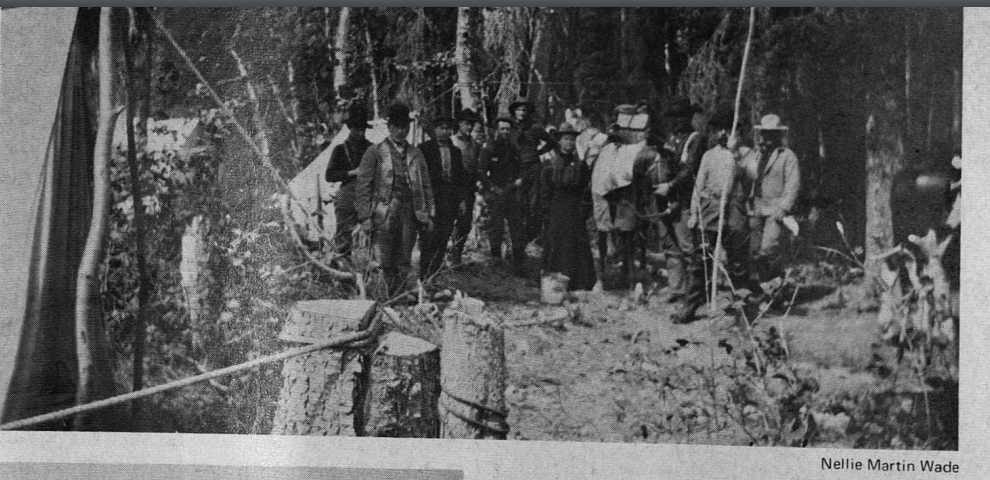

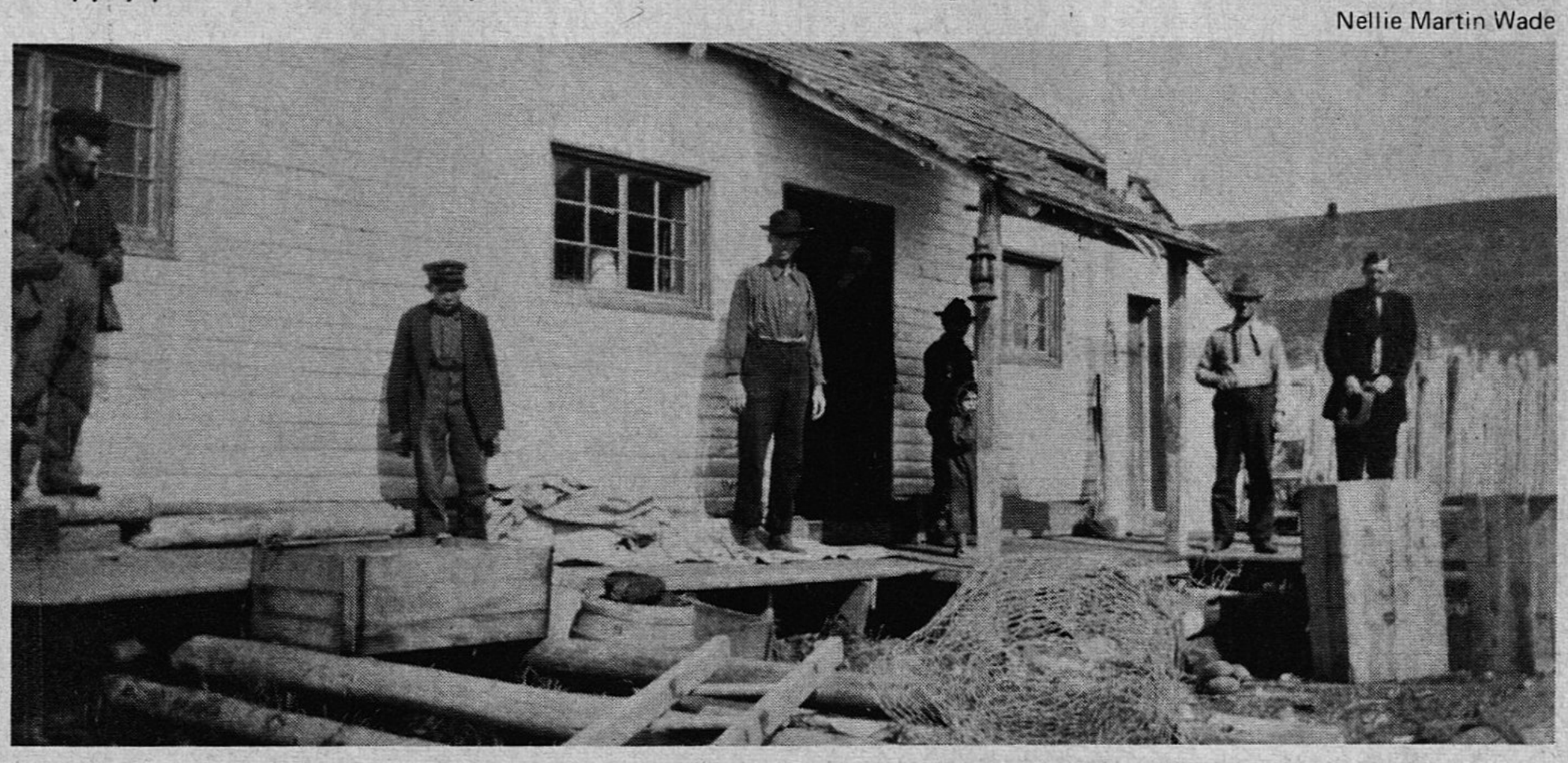

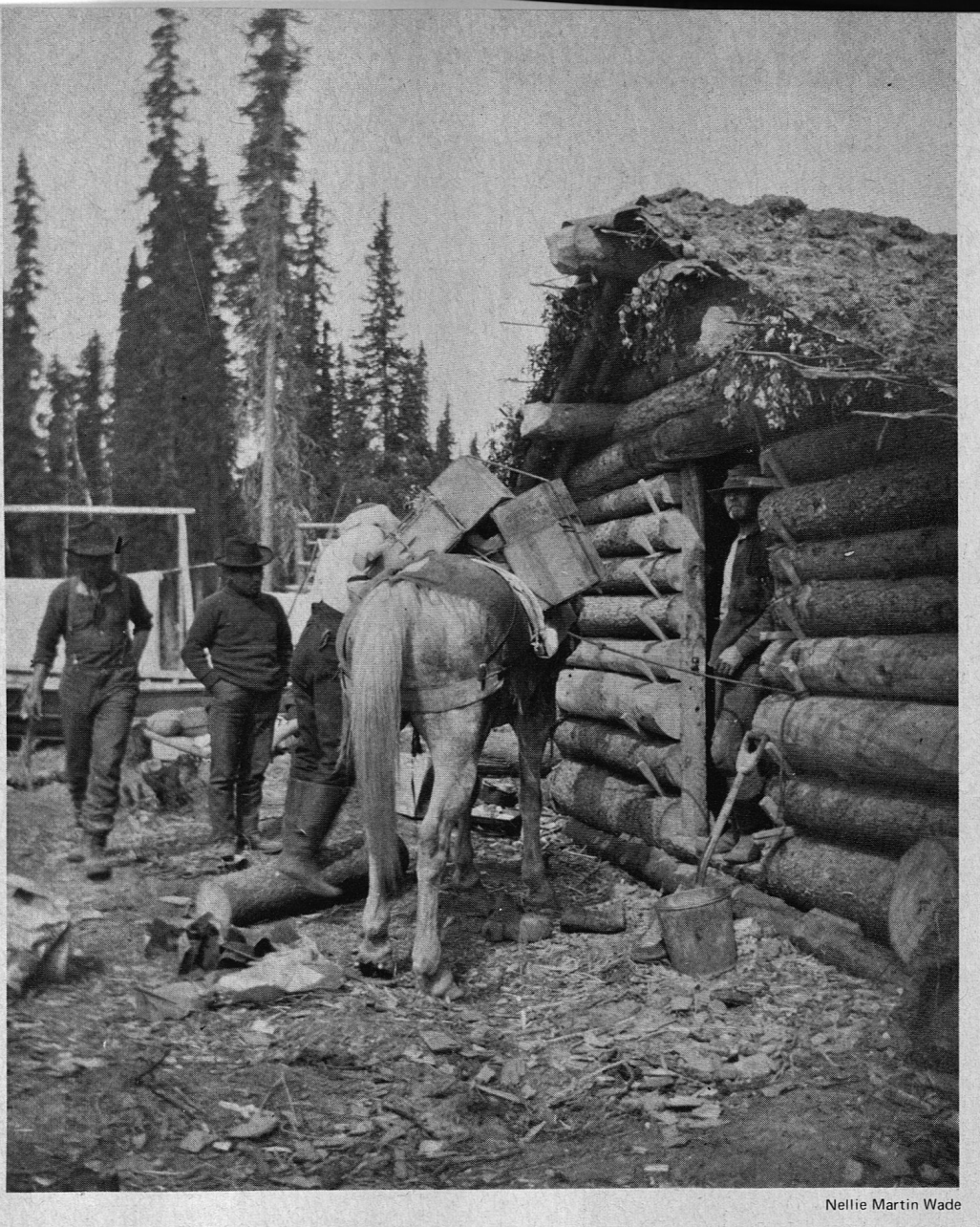

While researching the journey of the journal itself from Wade’s trip to the present day, I discovered an article from 1972 that contained excerpts from the journal and original photographs credited to Nellie Martin Wade. Though it is possible that these photos were not the ones intended for publication, they provide a clear representation of the towns, men, and nature encountered in Alaska.

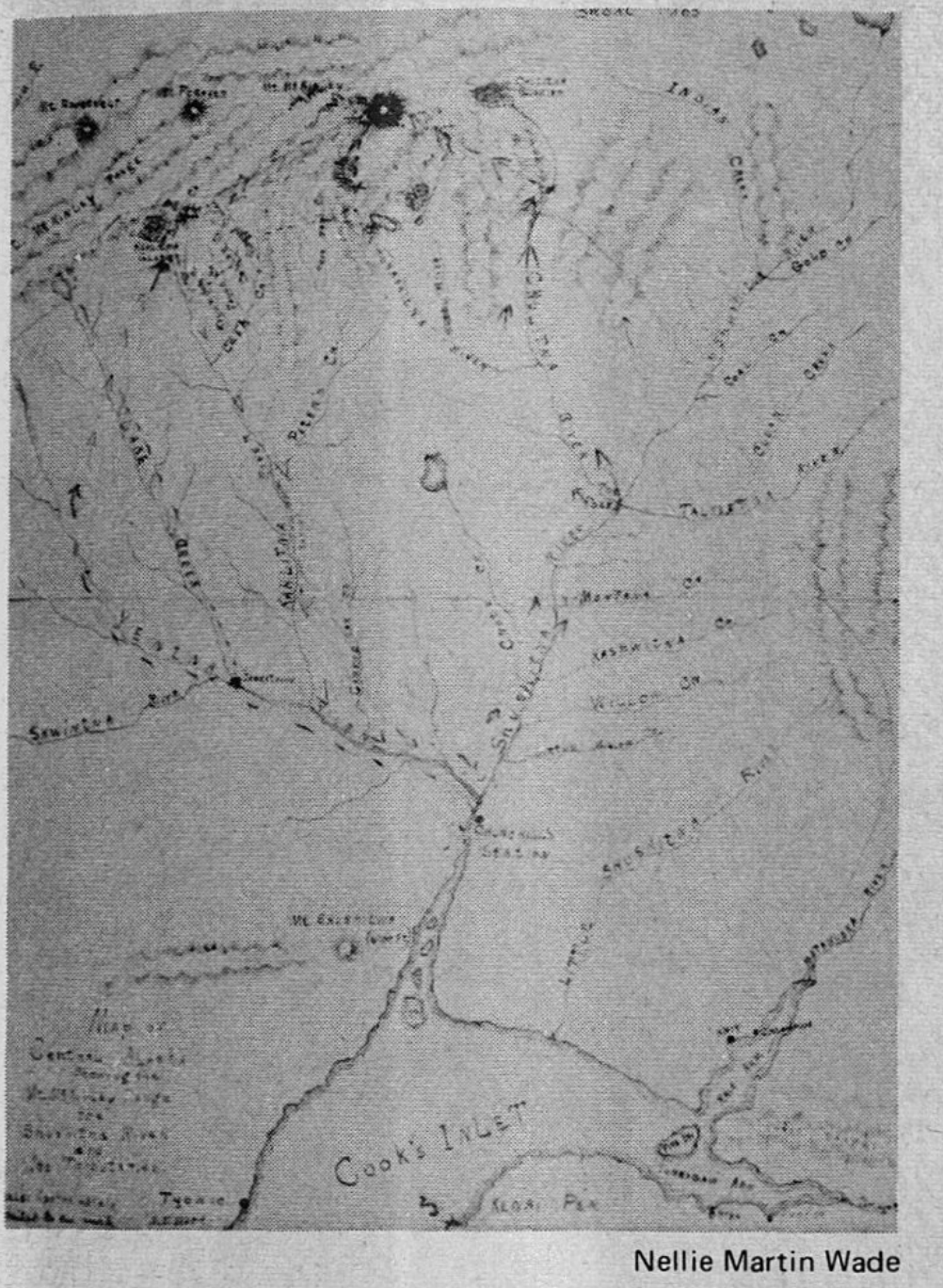

The article also includes a hand-drawn map by Waitman Wade, Nellie’s husband, of the Susitna Valley. While the labels are hard to read, the map signifies the detailed understanding that the Wades gained of the Alaskan landscape. To fully understand the role of hand-drawn work in these manuscripts, we now return to Thomas Adams’ journal.

Drawings

Thomas Adams includes many drawings and sketches of the landscape and of Indigenous people he encountered on his journey. Below is the map from the first page of the journal, which appears to be hand drawn with ink and watercolors.

Here’s the map!

Here’s the map!

The map is a good representation of the tone of the rest of the journal; it is focused on the facts of the journey and has a practical use. Some of Adams’s sketches are more for the purposes of illustrating the things he encounters on his journey rather than to be explicitly practical; these images allow the journal to act more like a scrapbook at certain times than the dry logbook that it usually functions as. Below are several examples of such sketches from the journal.

But Wait, There’s More!

The box of Adams’s things in the Western Americana Collection at Firestone Library holds several journals. Throughout this project, we have been primarily focused on the journal in the collection simply titled Journal. However, there are several others in the collection, and the one titled Journal, Volume II is illustrated in more detail than the first.

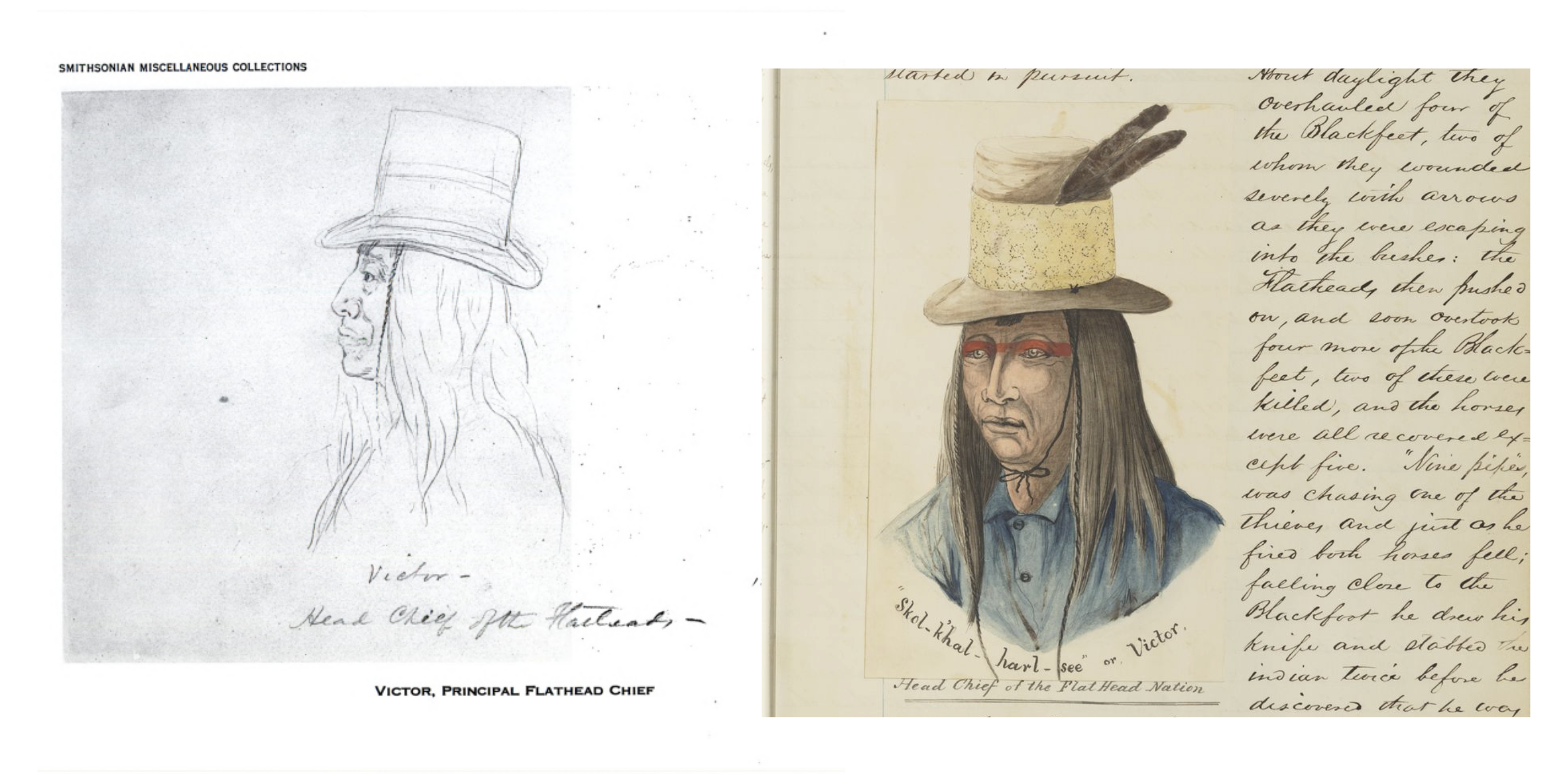

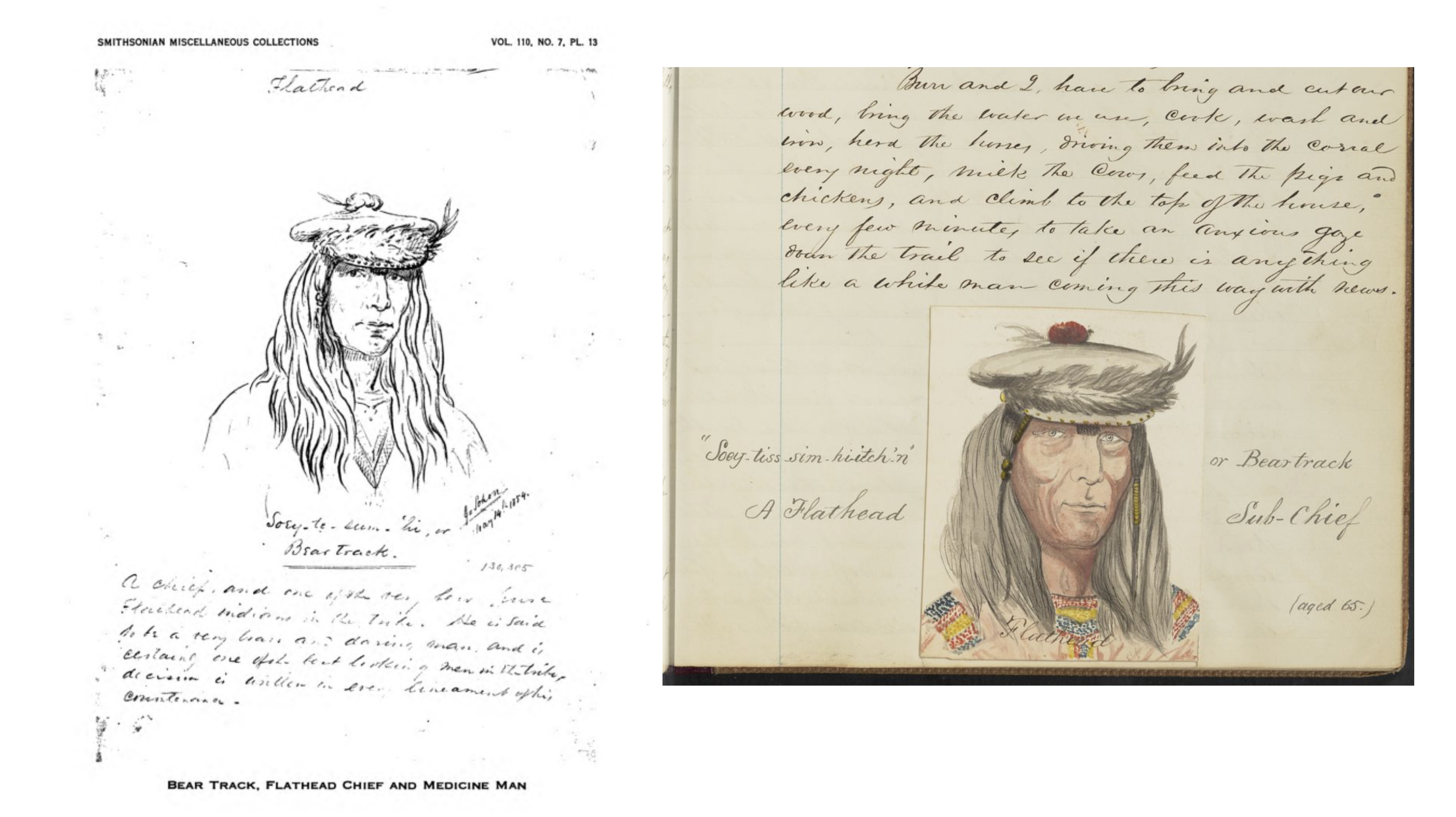

Enter Gustav Sohon! Born in Belgium, Sohon was trained in Germany and was an accomplished artist when he set out with the very Stevens Pacific Railroad Survey of which Thomas Adams was a part. In 1948, the Smithsonian Institution published Gustavus Sohon’s portraits of Flathead and Pend d’Oreille Indians, 1854 which, exactly as the title states, is a collection of Sohon’s portraits of Indigneous people during his time with the Stevens Pacific Railroad Survey. However, as pointed out by Gabriel Swift, curator of American Books and Western Americana in Special Collections at Firestone Library, some of Thomas Adams’s drawings look suspiciously similar to Sohon’s, specifically those in Journal, Volume II.

Take a look at the examples below. Notice how the names and the likenesses match up in an uncanny fashion.

On the left is the image from Sohon’s drawing, and on the right is Adams’ sketch.

On the left is the image from Sohon’s drawing, and on the right is Adams’ sketch.

Once again, Sohon’s drawing is on the left and Adams’ is on the right.

Once again, Sohon’s drawing is on the left and Adams’ is on the right.

Although there’s not really a definitive way to prove that the drawings were copied, the evidence certainly points to that assumption. But while the question of whether or not the drawings were copied is an interesting one, we do not have a conclusive answer.

References

“A Brief Guide to the Fireside Poets.” Academy of American Poets. Accessed May 9, 2021. https://poets.org/text/brief-guide-fireside-poets.

Adams, Thomas. “Journal.” Digital PUL, 1853-1854. Accessed May 9, 2021.https://dpul.princeton.edu/pudl0017/catalog/qr46r491g.

Adams, Thomas. “Volume II.” Digital PUL 1853-1854. Accessed May 9, 2021.https://dpul.princeton.edu/pudl0017/catalog/vh53x083j.

Bayers, Peter L. “Frederick Cook, Mountaineering in the Alaskan Wilderness, and the Regeneration of Progressive Era Masculinity.” Western American Literature 38, no. 2 (2003): 171–93. https://doi.org/10.1353/wal.2003.0032.

Cook, Frederick Albert. To the Top of the Continent; Discovery, Exploration and Adventure in Sub-Arctic Alaska. The First Ascent of Mt. McKinley, 1903-1906. New York, 1908. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/njp.32101020795371.

Ewers, John Canfield. Gustavus Sohon’s Portraits of Flathead and Pend d’Oreille Indians, 1854. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections.v. 110, No. 7. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1948. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001677793.

Martin, Naomi. “To Mt. McKinley On Horseback by Nellie Martin Wade.” Alaska: The Magazine of Life on the Last Frontier, June 1972.

“TEACHER AND STUDENT READING BIOGRAPHY OF GUSTAV SOHON.” https://www.washingtonhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Sohon-biography.pdf

Wade, Nellie Martin. “General Manuscripts Miscellaneous Collection (C0140) – Wade, Nellie Martin, ‘Through Interior Alaska on Horseback and the Scenic Coast Route’ Manuscript.” Princeton University Library Finding Aids. Accessed May 10, 2021. https://findingaids.princeton.edu/collections/C0140/c65810-06143.