Race and Eating Clubs

Racism in Imagery

The Princeton Bric-A-Brac refers to the yearbook that students used to put our every year. Within these year books, students would list the names of members of different organizations and also display drawings meant to show the character of the club.

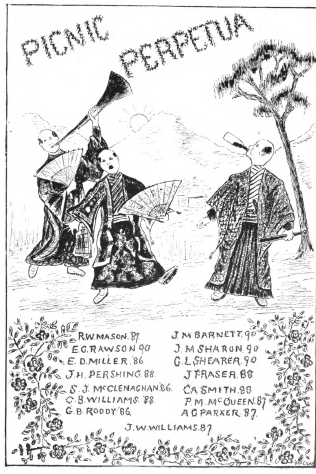

Eating club imagery was often included in these yearbooks. Unfortunately, some of this imagery would display racist caricatures. For example, the following two images used for eating clubs display caricatures of Asians and Native Americans in the 1890s.

The names of the clubs in the images do not correspond directly to eating clubs. In their early history, eating clubs sometimes still used the names and images from the more informal social groups that were their precursors when submitting images to the yearbook. However, they were still meant to be representative of the eating clubs, and the images are found under the eating club chapter of Bric-A-Brac.

At this point in Princeton’s history there were little to no Native Americans or Asians around campus. However, these images were still used. This situation demonstrates the racist attitudes held by members of eating clubs.

The stereotypes they seem to enjoy are particularly concerning given that they did not interact with people of color that they were using as caricatures. This early history demonstrates that from the start eating clubs were not set up to be racially inclusive.

In addition to these caricatures, there are several yearbook images from the 1890s that show black people only as servers. This trend of black people being seen almost exclusively as workers is something that continued to plague eating clubs later on. For instance, in his oral history about his time at Princeton, Alfred Price ‘69 discusses how many black students were on financial aid and often worked in the dining areas. As a result, many black students did not feel comfortable as members of eating clubs.

Not Wanting to Engage

As Princeton’s student population became more diverse, it may seem initially surprising that eating clubs often did not reflect this diversity.

However, students of color often describe feeling odd in the environment of eating clubs.

Robert Collins ‘71 explained in his oral history that he did not want to go through the process of joining a club because he did not want to be “scrutinized and picked over and chosen or rejected like that.” For him, the eating clubs represented “another lilywhite, male-dominated environment that was also not welcoming.”

This issue was not contained to the 1900s. For example, in a 2009 article entitled Race and The Street in the Daily Princetonian, Abiodun Azeez, a black student on campus explained that “the dining halls are definitely more diverse [than the clubs], the eating clubs are largely comprised of upper/upper-middle class white students, and so I think that it’s catered to what they as the majority want.” As a result, she was not going to join an eating club.

Even members of clubs discuss feeling uncomfortable about the lack of diversity. Lillian Chen ‘21 wrote an article about her experience being a member of four different clubs during her time at Princeton University. One of the clubs she joined was Colonial Club, which is known for having a lot of Asian members. While at first she described feeling more at home, Chen notes that “because I valued independence and diversity more than I valued comfort, I decided not to return to Colonial after that semester, despite genuinely liking the food and people there.” Thus, even if one feels welcome in the environment of an eating club, the lack of diversity can still lead students to not return.

Disadvantaged in Bicker

The lack of diversity in eating clubs also presented a problem for students interested in joining them. Alfred Prince ‘69 explains that the bicker process favored people who already had connections to clubs. For instance, athletes would encourage and help people on their teams to join their clubs. However, the low number of black students made it hard to gain the connections necessary to become a member of an eating club. Prince notes that although his memory might be faulty, during his “freshman year there were only eight [black upperclassmen] and none of them that I remember were members of clubs.”

Another black student named Trent Arthur ‘10 discusses how he has enjoyed his time as a member of Tower Club, but he is also noted that black students were at a disadvantage in bicker since there were not people in the clubs who looked like them and would help them to join.

An article in The Daily Princetonian from 2009 also notes that bicker clubs at the time were less diverse than their sign-in peers. This situation makes sense since bicker is a selective process in which people tend to pick others like them or people already in their social circles which can be segregated.

Even if people of color were able to join eating clubs, the act was often seen as a choice to assimilate into white culture rather than remain connected to people from their own racial background. For instance, a 1998 article in the Daily Princetonian documented that black students would sometimes refer to black students in clubs as “incog” which was short for “incognegro.”

A 2010 report from the university recommended that eating clubs work to have more initiatives that reach out to students of color so they feel welcome in the clubs and try to bicker. However, the bicker process is still criticized for creating inequality.