Parks as Spaces of Exclusion

Introduction

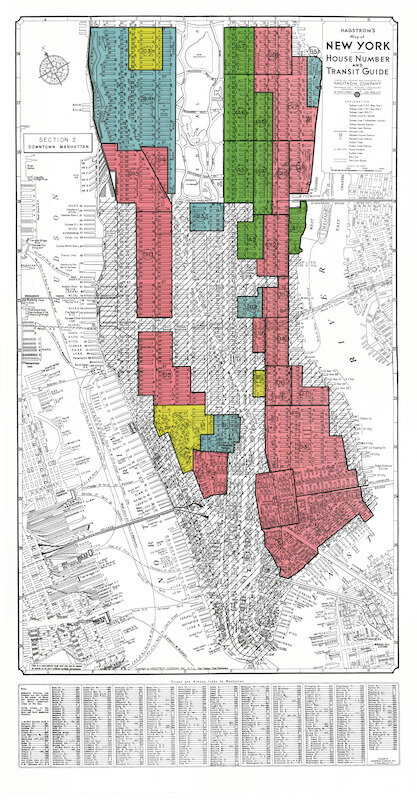

As we delve further into the digital humanities this semester, I am interested in exploring the development of public parks in 1930s New York and their roles in reifying and perpetuating social norms. The public park movement presented itself as a way to introduce open, green spaces into otherwise crowded, grey, concrete cities. But public parks acted as exclusionary spaces in the 1930s, both in their construction and patronage. Many of the iconic parks of New York such as Central Park were built in part by the Works Progress Administration of the New Deal and influenced by the City Beautification Movement, which promoted neo-classical building styles and Euro-centric models of beautification. At the same time as space was being created for the express purpose of leisure, the city of New York was itself undergoing changes in its composition. The Homeowners Loan Corporation, formed as a part of the New Deal, began categorizing neighborhoods according to how risky they believed loans to people in those neighborhoods would be. This marks the beginning of what we call today redlining, which served as a way of limiting the spaces in which poor people, people of color, and immigrants could exist. Thus, New York is undergoing this paradoxical change in the 1930s, wherein space is being both created and limited.

Both of these New Deal projects – public parks and redlining – radically transformed the landscape of New York City. They created separate realities for different city dwellers. The city of the 1930s New Yorker became even more dependent on where they lived, creating physical barriers of access within the city, centered primarily on class and race. Parks acted as a depiction of this separation, a place in which performance of social class and the associated norms and obligations became increasingly important.

Sources

I was browsing the digital collections in the Princeton Library when I came across Ho! For the Open Country: The Promise of the Public Park, curated by Emma Sarconi. This collection contains both plans for public parks as well as pictures of people enjoying the parks. The people depicted are all elegently dressed and seem to originate from a white, middle or upper class background. The collection speaks as well to the visions and influences of the landscape architects who undertook the projects, such as Frederick Law Olmsted and Ebenezer Howard.

This primary source collection is an important basis for my project, but I am also looking at maps of New York City from the same time period that are in the Lewis Library at Princeton University and currently available as a part of the online catalogue:

- The city of New York: Population

- The city of New York: Rental per Family Quarter

- The city of New York: Predominant Residential Type

- The city of New York: Predominnat Non-Residential Type

Reflections

These maps commissioned by the mayors’ office in 1935 provide context for the areas surrounding public parks as well as redlined neighborhoods. One possible limitation, though, is that these maps are a static representation of the year 1935 and do not depict the demographic changes to the city before or after this period. They also contain statistics from which we can extrapolate an understanding of the socio-economic situations within the city, but topographical representations of New York do not capture the dynamics inherent to the city and its undergoing transformation.

In addition to these primary sources, I am planning on integrating some of the scholarship that I have found about public parks and exclusion. William O’Brien’s book, “Landscapes of Exclusion: State Parks and Jim Crow in the American South,” will serve as an important first step in my research. His work focuses mostly on physical and legal exclusion, which is important, but I would also like to find more about the cultivation of public parks through practices such as promenading and picnicking to form spaces made for the white elite of New York.

Capturing the dynamic nature of physical transformation and the socio-political discourse and dynamics will probably present the greatest challenge to the project. Finding more pictures like the ones in the Ho! For the Open Country collection will be paramount as they give important insight into the nature and use of parks at the time.